The Problem of “γενεὰ αὕτη” (“this generation”) and

“πάντα ταῦτα” (“these things”) in Matthew 24

Part 1 - http://freedthinkerpodcast.blogspot.com/2011/05/did-jesus-predict-rapture-within-40.html?m=1

Part 2 – Sensus Plenior and Progressive Revelation

Introduction

Before I continue on with an examination of the specific passage under discussion, it seems necessary to take a step back and make some methodological and theological qualifications that will be of significant importance to our examination of the text. While entire books can and have been written on the topics of this section of our discussion, due to the limited space my treatment of it here will be almost hopelessly brief. However we simply cannot proceed any further without at least an introductory knowledge of these topics.

Within hermeneutics (the art and science of interpretation) theologians have long recognized the literary use of typology in Hebrew literature. While it is present and even prevalent in other texts besides the Bible, one simply cannot adequately read the Bible without recognizing the wide spread, and often foundational uses of sensus plenior in types (shadows), theme resolution, and double fulfillment. The import of these various hermeneutical methods may not be immediately clear until they are applied in further sections of this series. Since I am seeking brevity to a degree, this section will primarily involve some brief definitions and then several examples from Biblical passages to illustrate their usage.

Progressive Revelation

Genesis 3:15 has long been dubbed the Proto-Evangelion, which translates to the “first gospel.” However useful this title is for this specific verse is beside the point. What is of importance to our discussion here is that it is a prime example of what Christians mean when we talk about progressive revelation. Genesis 3:15 reads,

15 And I will put enmity

Between you and the woman,

And between your seed and her seed;

He shall bruise you on the head,

And you shall bruise him on the heel.

Between you and the woman,

And between your seed and her seed;

He shall bruise you on the head,

And you shall bruise him on the heel.

Here we find God pronouncing his judgment on the serpent for his role in instigating the fall of humanity into sin and death. This curse is at the same time immediate and eschatological. It is like a judge pounding his hammer in sentencing capital punishment, but without reference to the date of execution. From this day forth the serpent is on death row, desperately raging against the dying of the light. Christians have long seen this as the very first Biblical proclamation of the victory that will be achieved by Jesus’ death on the cross. They notice that it will be a human (seed of the woman) who will be the final victor over Satan. And while the serpent may bruise the heel of Christ (when he dies for a time) it will ultimately be that very heel that crushes the head the of the serpent. Yet what we notice instantly from a passage like this is that not everything that can be said is mentioned about this struggle between the powers and principalities of this world and the people of God throughout history. Not everything that can be said about the reason for or the outcome of the death and resurrection of Jesus can be found within Genesis 3:15. It makes no mention of the substitutionary nature of the atonement, the sheer grace of God’s election, justification or sanctification of believers. Nothing is said to the effect that we are only saved by grace, through faith, and not by works. In fact, the proto-evangelion is only a slightest foreshadow of the later reality, the most minute taste of the what is to come. Yet it is vitally important to driving the narrative of redemption of the first Adam to the second. It propels the story forward as the people of God, languishing under sin, death and condemnation, constantly look to the hills for the first sign of the coming savior, the seed of the woman who was promised, the Anointed One, the Christ.

And it is in this propulsion that the concept of progressive revelation is most prominent. We see that God did not desire to reveal everything that there is to know about himself, about us, about the cosmos, about sin and death and redemption. In fact, what we find over and over is that God is God who is pleased to address his people in their historic context, condescend to speak to them in language accessible to them, and to reveal as much of himself as is needed to guide the people of that time forward toward redemption. We must remember that there was a time when not everyone had the full counsel of a complete Bible to inform their lives. They lived at a certain time in history in which the world was viewed entirely differently than how we view it today. The ancient world had different views of the nature of the cosmos, the meaning of life, the priorities of daily life, of government, religion, culture, and even a fundamentally different worldview. For example, it becomes almost impossible for us to understand the world of Genesis 1 through the functional ontology of the time, because we are so steeped in a modern, scientifically driven material ontology.

This is all to say that God spoke to people where they were. He did not require them to change their cognitive structures, worldviews, or cultures in an instant just to understand who God was, what humanity’s place in the cosmos was, and what God was doing in history. When missionaries go into other cultures they often have to “contextualize” their message in order to effectively minister in a foreign culture. This means that they must find a way to communicate using that culture’s language, history, worldview and iconography but maintain the core message that they want to convey. We could say that God was the ultimate contextualizer. God did not give lectures about everything that a person would need to know about the nature of the universe, of matter, of disease, of evolution, of science, art, literature, morality, etc. God gave us stories. And in a sense, a story can more easily endure, transcend, motivate and undermine any one culture to appreciated the world over.

This then brings us to our main area of discussion for this section. That God, being the grand author, the one who saw redemptive history from beginning to end, like a master story crafter, sets certain balls in motion that will find fuller significance later in the story. This really is a sign of a master literary mind. How often have you marveled when reading your favorite book or watching your favorite movie, that you notice something that seemed so trivial or at least less than profound coming to a full blossom at the dénouement of the story; when all loose ends are fastened and all questions answered. Even the stories that end with a mystery, a question, a new quest for the truth, are so powerful because they have been building toward such a conclusion – the quest, the question itself had been there the entire time, lurking in the shadows; growing, building, gaining speed and significance. This is the difference between stories where the climax fails, at which we are angered to have wasted our time on the story, and the ones that the ending question excites us to delve into the story again in a perpetual quest for answers that we know will never come. It is only when we realize that the story itself is fully expressed in the quest, that it all points to the fact that in the end there will be no finish line, just another bend in the road, that we fully appreciate these stories.

Should it not surprise us then that the Bible, “the greatest story ever told,” should have elements of both? That a theme or an image or event that seemed to have one significance early in the story should come to full blossom to another in its climax? But that it would also lead us so powerfully to a quest? To unanswered questions? Is it not fitting that Revelation, the final book in the canon, should be so littered with Old Testament imagery that the only way to really understand it is to start over at the beginning of the narrative, when God created the heavens and earth that came to renewal at the close of Revelation?

Before moving on we should note however that progressive revelation is not quite the same as an evolved revelation. It does not mean that what is said early in the story evolves or changes as the story progresses. As we will see, what can be considered a type will go unmentioned for nearly the entire canon before it gets picked up again. It does not go through changes. It is simply planted, germinates, then blossoms in its full splendor later on. It also does not mean that God will say one thing early in the narrative, change his mind, and say something later. While some skeptics want to say that the Bible will often contradict previous statements, I am fairly convinced that this is simply not the case, and I have never been presented with any veridical examples of it. (The examples are often given by those of very little education in material they are addressing, following a total lack or even explicit rejection of study of the historical, cultural, theological and linguistic contexts of the passage, based on inexcusably shallow interpretations of the ENGLISH text, and without any awareness of their own ineptitude.)

Sensus Plenior

Sensus plenior (SP) in Bible is actually a kind of umbrella category for the other terms that will follow as they are more specific applications of SP. Sensus plenior is a latin term that means, literally, “fuller sense” or “deeper meaning” and is used to refer to those passages that speak of a person(s), event, or theme that has an immediate meaning in its original context but that looks beyond them to a fuller or deeper realization, recapitulation, application or resolution in a future person(s) or event. While some definitions treat these meanings are primary and secondary meaning, I find these categories to be less than helpful since the secondary (plenary) meaning often has a more weighty importance in the overall scope of the Bible.

SP is often expressed in terms of typology, theme-resolution, and double fulfillment. Here I will only be giving a brief definition of each followed by an example or two for each. I recognize that entire books can and have been written on these issues and that the extent to which we should observe each of these in Scripture is hotly debated, and thus am under no delusion that the remainder of this section will be a sufficient treatment of these topics. What I am hoping for however is simply to present the concepts as they will be employed in our later discussion of Jesus’ statements in Matthew 24 and other passages we will explore.

Two major expressions of SP are typology and double fulfillment. (There are others such as theme fulfillment, metaphor, etc. but we are only concerned to address these two here.)

1. Typology

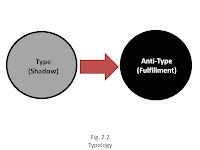

a. A prior person, place or event is the prototype or indicator of a future antitype. Theologians also talk in terms of “shadow” and “fulfillment” when addressing these passages.

b. Examples:

i. Adam – This is a common example and one that Paul in Romans 5 himself teases out. We see that while Adam was the first human to enter into a covenantal relationship with God, that Jesus is the fulfillment of that. Where Adam broke the covenant and brought death to all those whom he represented in the covenant of works after him, Jesus succeeded and brought life to all those whom he represented in the covenant of redemption. Adam’s failure as a covenant breaker, pointed toward the need for a covenant keeper. Adam as the bringer of death, pointed toward one who would be the bringer of life.

ii. Israel – Where Israel wandered and failed for 40 years in the desert, Jesus was directed and succeeded in the wilderness for 40 days. Where the Israelites sinned in their disdain for the bread that God had provided for them, Jesus succeeded in his love for the bread (the word of God) that he had been provided. Where Israel was called like a “son” by God when called from Egypt (Hosea 11:1-4), Jesus was God’s son whom was called as a child out of Egypt.

iii. Prophet, Priest and King – A prophet was one who spoke to the people for God. Jesus spoke to the people as God. A priest was one who interceded for the people before God, Jesus interceded as God for the people. A priest needed to atone for themselves before they brought an offering to God that was imperfect and would only suffice for a time. Jesus was the perfect priest who needed no cleansing or atonement for himself and who offered the perfect sacrifice once and for all. The king ruled over Israel under the guidance of God in attempt to bring about justice and righteousness but only ruled for a time, and often unsuccessfully. Jesus is the eternal king who rules as God in perfect justice and righteousness.

2. Double Fulfillment

a. A statement, prophecy or theme may have not only an immediate application but will also have perpetual later application as history unfolds. A common illustration given to show what is meant here is that of a mountain range. In fig. 2.4 we see first a mountain from a great distance. It appears to be far off but when we draw closer we find that it is not only one mountain, but a range of mountains. So with double fulfillment it is that the author may see only one fulfillment when they pen their verses, but as history unfolds we find that there may be several actualized fulfillments of the verse. What is important to note here however is that contained within the original contexts of the passages are hints that it is referring to more than one fulfillment.

b. Examples

i. Immanuel. In Isaiah 7 we find this statement: 4Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign. Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel. 15He shall eat curds and honey when he knows how to refuse the evil and choose the good. 16 For before the boy knows how to refuse the evil and choose the good, the land whose two kings you dread will be deserted. 17 The LORD will bring upon you and upon your people and upon your father’s house such days as have not come since the day that Ephraim departed from Judah—the king of Assyria."

Many people have done wonderful work on full expositions of this text and I myself preached an entire sermon on it (listen to it here: http://logical-theism.blogspot.com/2010/08/ahaz-at-crossroads-isaiah-71-17.html). Here I am simply going to state that the Immanuel child was likely a child born to the prophet prior to Judah’s fall to the Assyrian King Tiglath Pileser III. Yet when we look at the passage we can see that this child could not have been the only referent of the passage. As we keep reading further down past the citation above, we see that the child points to another child, another Immanuel. Not a child who would show us “Immanuel” (“God with us”) but a child who would actually be Immanuel. A child who would be God come to dwell among us. (Incidentally this points us also to the significance of the tabernacle. God would dwell with his people in the tabernacle, but would later quite literally dwell with his people in the person of Jesus.)

ii. The abomination that causes desolation. Daniel 9:27 says, And he will make a firm covenant with the many for one week, but in the middle of the week he will put a stop to sacrifice and grain offering; and on the wing of abominations will come one who makes desolate, even until a complete destruction, one that is decreed, is poured out on the one who makes desolate.” While commentators go back and forth about what is actually meant, what they all agree on is that what is being referred to is an act that is considered “unclean” by the Jews being performed in the temple. This text will be vital to our later discussion so I will be very brief here, but we can ask, when was this or will it be fulfilled? Well some want to say that it refers to Antiochus IV Epiphanes in the mid-second century BCE. Antiochus had set up an alter to Zeus in the Second Temple and then to add insult to injury, sacrificed a pig on the alter of God sometime around 167 BCE. Other scholars point to a similar incident with the Romans who destroyed Jerusalem and set up the standards of the Emperor (considered by many to be divine) in the temple courts. Other scholars would look a few years previous to Nero, while others look to a future Antichrist who will fit the bill. Some see it in Hitler, others Stalin, some Bin Ladin. Others think he has yet to be identified. The problem here is that each of these commentators is looking for one and only one fulfillment While it is possible that none of these are the events that Daniel was referring to, it is possible that each of these (admittedly more drastic than the previous one) are growing fulfillments of the passage? In fact when we look at John’s 1st epistle we see that he does not have in his mind one single Antichrist but says that “it is the last hour, and as you have heard that antichrist is coming, so now many antichrists have come” (1 John 2:18). Does this mean that John does not think that there will not be one final and antitypal antichrist? Not at all. But it does show that John is comfortable identifying many fulfillments of the antichrist motif. It is possible that he has Antiochus, Nero, the Roman armies and a future Antichrist in mind.

Now that we have examined (though admittedly extremely briefly) these concepts, we will be prepared in our next section to begin our examination of the interpretation of the Olivet Discourse in Matthew 24 that I find to be most compelling; not because it simply “works” to save an inerrantist view of the Bible, but because it is the most plausible interpretation given the theology, hermeneutic, and worldview of a 1st century Jewish teacher like Jesus.

In the following sections I will be arguing that Jesus did intend his statements to be fulfilled within approximately 40 years but that what he was referring to was not his Second Coming or the end of the world, but to the coming of the kingdom of God as expressed in the judgment and destruction of the temple in CE 70. In addition, Jesus most likely was using typology and double fulfillment to point beyond these events to fuller and more complete realizations of these events. As he was warning his listeners to be prepared and well equipped for the end of Jerusalem which they could see the signs for and be ready for (thus the warning to head to the hills which would be utterly futile at the end of the world), how much more so should they attempt to prepare their souls for the final coming of Jesus to usher in culmination of all redemptive history? I intend to show that Jesus did not falsely predict anything, but was rather using an event such as the judgment on Jerusalem to point beyond itself to a greater eschatological reality.

For further study on these topics I recommend the following books:

The Shadow of Christ in the Law of Moses by Vern Poythress

Preaching the Whole Bible as Christian Scripture by Graeme Goldsworthy

Gospel Centered Hermeneutics by Graeme Goldsworthy

Knowing Scripture by R.C. Sproul

Look to the Rock by Alec Motyer

Primary and Plenary Sense by F.F. Bruce (article) http://www.biblicalstudies.org.uk/pdf/plenary-sense_bruce.pdf