"Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent."

-Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

For those who have been around the Theist/Atheist debates, the term Dunning-Kruger Effect may be a term that is familiar and yet undefined for many of you. For those of you who are not familiar with the term, let me briefly describe what it is.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect (DKE) is the thesis put forward by two Cornell University psychologists, David Dunning and Justin Kruger. Through various experiments on lab rats (i.e. undergrad students) they attempted to show that there exists a certain kind of cognitive bias whereby certain “unskilled” individuals tend to assess their abilities and skills as higher than what they actually are. The researchers credit this increased confidence to a “metacognitive” inability for them to recognize their own lack of ability. Some people mistakenly think that DKE just means that someone is wrong but thinks that they are right. That is an incomplete understanding of the thesis. DKE goes further and postulates that it is precisely the skills that one would have learned had they been properly educated or trained in a field, that are the exact skills one would need in order to identify the fact that they are unskilled in said field in the first place.

As Dunning so succinctly put it, “If you’re incompetent, you can’t know you’re incompetent… the skills you need to produce a right answer are exactly the skills you need to recognize what a right answer is.” In other words, unskilled people fail to realize that they are unskilled because one of the skills which they lack is precisely the skill needed to differentiate between skilled and unskilled in a given field. It’s a tongue twister, I know. Many of you may have engaged with people in discussion or debate and been so frustrated by their apparent lack of understanding coupled with their simultaneous overestimation of their own skill or knowledge, and yet you were not able to describe exactly what was going on. Well, what you were observing was likely the DKE in effect.

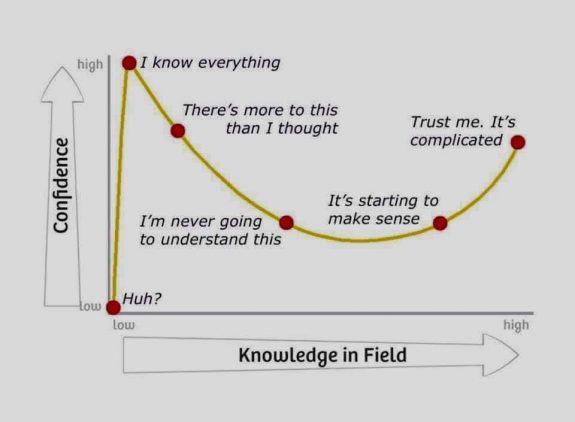

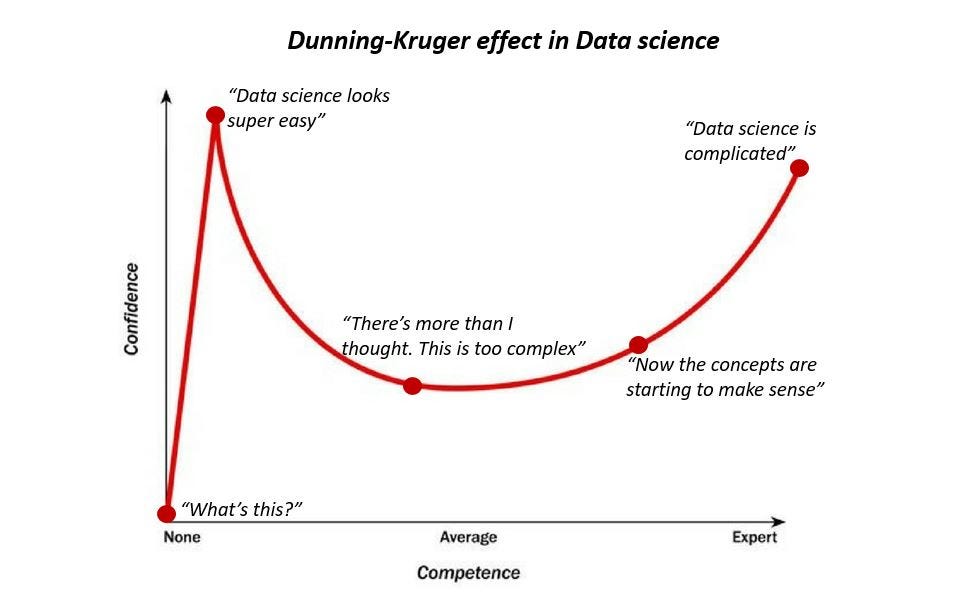

There are various ways to graph out a visual representation of DKE, ranging from the serious to the comical. Some examples are:

Where someone would fall on this graph is largely measurable by using various metrics. The list that I am about to give you is the DKE indicators and the justifications presented by Dunning and Kruger. You will notice that each indicator is then expanded upon and clarified within a corresponding comment from J. Burke. It is important to note that these indicators function much more like a spectrum of severity that a person could fall somewhere along, and thus someone could suffer from DKE to greater or lesser degrees depending on the field in question and it could be expressed to greater or lesser degrees across these eight indicators. The idea is that the more of these indicators a person exhibits, and to a stronger degree, the more probable it is that such a person is suffering from DKE. The following layout for these indicators and the initial references I am getting from J. Burke.

The eight indicators of DKE are:

1. Skill-boundary Transgression: The individual is seeking to operate as an authority or qualified individual, in a field beyond their personal level of academic and professional qualification.

a. “Incompetent individuals, compared with their more competent peers, will dramatically overestimate their ability and performance relative to objective criteria.’, ibid., p. 1122; the importance of formal academic and professional qualifications is that they constitute objective criteria by which competency can be assessed, so we should place less trust in those lacking such qualifications.”

2. Self-identified Authority: The individual identifies themselves as sufficiently competent to comment authoritatively on the subject.

a. “These findings suggest that unaccomplished individuals do not possess the degree of metacognitive skills necessary for accurate self-assessment that their more accomplished counterparts possess,’ ibid., p. 1122; we cannot rely on those who are not academically and professionally qualified in a particular field, to assess accurately their own authority and competence in that field.”

3. Unrecognized Competence: The individual’s self-assessed competence is not recognized by those who are academically and professional competent.

a. “We propose that those with limited knowledge in a domain suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach mistaken conclusions and make regrettable errors, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to recognize it.’, p. 1132;. it is far more likely that an unqualified non-professional will be wrong in a given field of specialization, than a qualified professional whose competency has been recognized formally by their equally qualified peers.”

4. False Peers: The individual believes that the favorable commentary of other unskilled and non-professional individuals, indicates they themselves are sufficiently qualified.

a. “… some tasks and settings preclude people from receiving self-correcting information that would reveal the suboptimal nature of their decisions (Einhorn, 1982).’, ibid., p. 1131; by keeping themselves predominantly in the intellectual company of those who agree with them, individuals experiencing the Dunning-Kruger Effect place themselves in a setting which typically prevents their errors being exposed, instead keeping them in a kind of intellectual echo chamber in which their views are reinforced by being repeated back to them with approval by those unqualified to assess them competently.”

5. Scrutiny Avoidance: The individual fails to submit their work for professional scrutiny (such as in the relevant scholarly literature), for review by those genuinely qualified.

a. “One reason is that people seldom receive negative feedback about their skills and abilities from others in everyday life (Blumberg, 1972; Darley & Fazio, 1980; Goffman, 1955; Matlin & Stang, 1978; Tesser & Rosen, 1975)’, ibid., p. 1131; avoidance of scrutiny by professionals enhances this effect, keeping the unqualified away from those who are best able to expose their errors, and preserving their self-delusion that they are correct.”

6. Pioneer Complex: The individual self-identifies as a pioneer uncovering previously unknown or unrecognized facts; a Copernicus or Galileo.

a. “This is a self-delusional identification since neither Copernicus nor Galileo were ‘gifted amateurs’ opposing a body of professionals (both men were professionals, holding formal teaching positions), and Galileo in particular knew that the subject should be decided by professionals astronomers, placing no value whatsoever on the opinions of the unqualified; writing against the papal edict silencing publications on heliocentrism in the preface of his ‘Dialogue’ (1632), Galileo scorned the unqualified amateur: ‘Complaints were to be heard that advisors who were totally unskilled in astronomical observations ought not to clip the wings of reflective intellects by means of rash prohibitions.’, Galileo, quoted in Næss, ‘Galileo Galilei: When the Earth Stood Still’, p. 131 (2005).

7. Conspiracy Claims: The individual explains opposition by qualified professionals as a coordinated attempt to suppress truth, in order to defend the existing scholarly consensus.

a. ‘Third, even if people receive negative feedback, they still must come to an accurate understanding of why that failure has occurred. The problem with failure is that it is subject to more attritional ambiguity to success. For success to occur, many things must go right: The person must be skilled, apply effort, and perhaps be a bit lucky. For failure to occur, the lack of any one of these components is sufficient. Because of this, even if people receive feedback that points to a lack of skill, they may attribute it to some other factor (Snyder, Higgins, & Stucky, 1983; Snyder, Shenkel, & Lowry, 1977).’, ibid., p. 1131; when an unqualified non-professional attributes opposition to or dismissal of their theories by qualified professionals as a conspiracy to maintain the intellectual status quo, the Dunning-Kruger effect is very likely responsible: an example is the Science and Public Policy Institute(a non- profit group in the US which opposes the scientific consensus on global warming), ‘People who are not scientists, or even experts on the subjects they write about often write the SPPI reports, and many convey conspiratorial themes. For example, an SPPI publication by Joanne Nova, who describes herself as a “freelance science presenter, writer, & former TV host”, exemplifies not only the ‘Dunning-Kruger’ effect (Dunning et.al. 2003), but also the inactivist movement’s frustration with mainstream climate science and its inflated sense of victimhood.’, Elshof, ‘Can Education Overcome Climate Change Inactivism?’, Journal for Activism in Science and Technology Education (3.1.25), 2011

8. Allocentric Claim of Bias: The individual explains the difference between their views and those of qualified professionals, as the result of inherent bias on the part of the professionals; accusations of bias are directed at anyone other than themselves, and they claim objectivity.

a. Allocentric means ‘focused on others’, or ‘aimed at others’.

Here it is important to note that before one begins to evaluate the statements made by some individual, they should realize that unless they are a trained psychologist they should not attempt a definitive diagnosis. The irony of doing that with DKE itself, may rip the very fabric of nature apart. So let me be clear that when I think that someone is exhibiting indicators that they are being guided by a kind of DKE , I do not pretend to be qualified to make such a strong evaluation of this individual as an actual diagnosis. Rather, my comments in this regard are simple facts about the kinds of actions and statements that this person publicly presents which lead me to think that the DKE t is likely a robust explanation for these features of their statements. It is a framework that seems to fit well with the majority of the data but in no way should be construed as me trying to actually diagnosis them.

Observing that someone is experiencing the DKE also does not mean that such a person is unintelligent. I am fully convinced that individuals who are quite intelligent and well versed in some topics, can be completely biased in others, which is partly what leads to the frustration that occur in these conversations. The DKE applies to areas where an individual is unskilled or has not undergone adequate or comprehensive academic or technical training to merit their level of confidence in their assertions on the topic or about actual experts in that field. So I do not mean this as a slight against any person’s character or to insinuate that they are unintelligent or immoral.

I am sure that observers and participants on both sides of these discussions (and often on both sides of any contentious issue) will be able to think of numerous examples of when they have observed the DKE in action. I find that generally asking, “What academic or scholarly literature have you read that informs your understanding of X,” is a helpful indicator, though not an all-purpose tool. More often than not, people who appear to clearly be suffering from DKE will have made very strong claims with regard to X, even telling people who do have higher levels of academic familiarity with X that their views of it are stupid or unevidenced, to which their level of dogmatic certainty is simply unwarranted by the little to no research that they have actually performed. Once asked the question, rather than admitting that they have simply not studied and then realizing that they should moderate their beliefs, the person exhibiting signs of DKE will instead go on the offensive ridiculing the question, claiming that they do not need to study because the literature is all written by advocates of X anyway, claiming that they have studied the data themselves and don’t need to read any experts, or try a tu quoque maneuver asking if the questioner has read all the literature that there is to read to know that they are wrong.

Here I am not making any claims as to who is guilty and who isnt or casting any blame. I merely want to give the tools for people to analyze why some of these conversations turn out to be non-productive, and to remind us that we ought to moderate our psychological states of conviction, certainty, and dogmatism in accord with the levels of research that we have actually completed into a field.

RESOURCES

1. Burke, J. https://bibleapologetics.wordpress.com/tag/intellectual-honesty/

2. Kruger & Dunning, ‘Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (77.6.1132), 1999

3. Morris, Errol (20 June 2010). "The Anosognosic's Dilemma: Something's Wrong but You'll Never Know What It Is (Part 1)". New York Times.